The world is not aware of how healthcare innovation occurs

SAD BUT TRUE

The world is not aware of how healthcare innovation occurs, and frankly, it has lost appreciation for it. I know this because I was guilty of this until recently. I focused on the high price of new treatments at launch and didn’t acknowledge their benefits that can persist long after their high price. I was not alone in this thinking. More than 80% of adults believe that the costs of prescription drugs are unreasonable. I am assuming that when adults are thinking about the costs of prescription drugs, they are thinking of expensive branded drugs rather than cheap generics, although 90% of all filled prescriptions are generic drugs. I was guilty of this lack of appreciation for generics.

I refer to myself as a health economist—I received graduate training in health economics a decade ago. But in my training, I was not taught how healthcare innovation occurs and the importance of it. I was taught that the US spends significantly more on healthcare than other wealthy countries. The scatterplot of US healthcare spending per capita as compared to other wealthy nations, with the US being a clear outlier, was a mainstay of my curriculum. I was taught that drug prices are much higher in the US than in other countries and that is a contributor as to why the US spends so much more on healthcare. I wasn’t taught what the high drug prices in the US provide society.

After engaging with investors and innovators, and committing to learning how innovation occurs, my perspective has completely changed. I now understand that the high prices the US pays for drugs incentivizes healthcare innovation globally.

Developing new treatments is extremely expensive and extremely risky. The approval rate of a Phase I drug is around 8%. So why would someone invest in something that had such a low probability of success? The answer is simple. The returns generated by the rare few that do get approved must be high enough to cover the losses of the majority that do not get approved. The few drugs that get approved and can be commercialized must make a lot of money over their patent protection period. Without a high return, the investment risk is no longer worth it, and investors would need to find other things to invest in.

So, yes, drug prices are higher in the US than in other countries—in fact the US makes up 44% of the global pharmaceutical sales despite representing only 4% of the global population. But these high prices provide high returns (for the select drugs that get approved and are commercial successes)—providing justification and funding for future high-risk investments in healthcare. Rather than seeing the US as an outlier in drug pricing as a negative thing, I now see the US as the keystone for continued innovation. Interestingly, the US also contributes to more than 40% of global military spending. We pay the price, so we don’t pay the price.

But here is the sad part. Things are changing. As Jason Shafrin, Lou Garrison, and I explain in a STAT First Opinion article, the US is getting fed up with paying higher prices for drugs, “becoming increasingly more sensitive to the idea that it may be overpaying for medicines”. We are living in a world with government price negotiation during the patent protection period and proposals for price to be a factor in considering march-in rights.

Given the huge impact the US market has on research and development, drug pricing policies in the US have an impact across the globe. US drug pricing policy impacts all of us. Policies that reduce returns over the patent protection period will have implications for future innovation. I’m not an investor, but I don’t need to be to know that “high risk-low return” doesn’t make sense.

There are serious inefficiencies in the United States healthcare system that need to be addressed, and we need to reduce out-of-pocket costs for patients. But we need to find ways to reduce these inefficiencies without reducing what we all want—more research and development leading to more treatments in the future. Could there be some optimal payment to innovators that is dynamically efficient and provides just enough payment to ensure the optimal rate of innovation? That’s certainly a noble goal, but I question its practicality. There seem to be easier, dare I say more efficient, ways to reduce inefficiencies in the US healthcare system without price controls over the patent protection period.

A key objective of the Center for Pharmacoeconomics will be to educate the public on how innovation occurs to shape a future where the public considers the value of future generics.

WE DID IT AGAIN

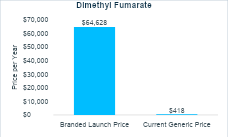

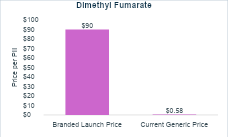

Expensive branded drugs will likely become cheap generics that can benefit society long after their patent protection period. Let’s look at Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate). Tecfidera was approved in 2013 at a launch price of $75 per pill. Inflated to present US dollars, that’s around $90 per pill or nearly $65,000 per year. Today, 11 years later, you can buy a generic version of dimethyl fumarate for $0.58 per pill or a little more than $400 per year (see the charts below).

It is worth noting that generic competition entered early for Tecfidera due to patent challenges. We will discuss the importance of patent protections extensively in upcoming newsletters, but this example demonstrates two things—generic competition can drive down prices and developing drugs is extremely risky.

The fact that branded drug prices should only be high for a finite period is important for policy making and for public perception around drug pricing. It also really matters for cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost-effectiveness analyses evaluate the costs and consequences of a new treatment typically over a long period of time—often the lifetime of a patient who starts the treatment. Although these analyses typically forecast costs and consequences far into the future—often decades—they almost never account for future genericization. Rather it is conventional practice to keep a drug’s price constant over the entire time horizon, ignoring expected price changes due to eventual genericization.

For a cost-effectiveness analysis conducted for a new treatment around the time it is launched, which is when most cost-effectiveness analyses are conducted, the analysis would likely assume the high launch price would persist indefinitely. In the case of dimethyl fumarate, this would substantially overestimate the treatment costs and could lead someone to conclude that it is not a good use of resources. However, in the case of dimethyl fumarate, the price dropped 99% within eleven years.

Methods have now been developed, and a preponderance of evidence is now available, to be able to incorporate future expected price changes in cost-effectiveness analysis. The Center for Pharmacoeconomics will be applying these novel methods to reflect the reality that prices of expensive branded drugs should eventually drop due to generic entry

TURN THE PAGE

The number of new clinical trials of previously approved drugs declined by more than 35% in the era of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). These preliminary findings presented by the National Pharmaceutical Council at a recent research conference suggests “an immediate and substantial reduction in the number and trend of post-approval clinical trial initiation post-IRA.” Their figure displayed here speaks for itself.

Although the Inflation Reduction Act was signed into law in 2022, it will take many years to have evidence to understand its impact on innovation due to the long development process that is characteristic of drugs. Many anticipate that the Inflation Reduction Act will disincentivize post-approval research and the preliminary findings from the National Pharmaceutical Council support this concern. Post-approval research and development is conducted to study the impact of an approved drug on different conditions, for different populations, etc., but the Inflation Reduction Act might disincentivize this expensive post-approval research due to the time frame for government price negotiation being shorter than the average time frame for generic competition, especially for small molecules.

SEEK AND DESTROY

Focusing on the high prices of a drug over its patent protection period is short-sighted. A perspective in the New England Journal of Medicine published earlier this month states, “Congress could substantially increase the government’s savings by allowing CMS to negotiate prices sooner after new drugs are approved.”

At first read, that seems like an obvious statement. If negotiations started earlier, there would be more cost savings. However, that exact thinking is what I was referring to in the first section of this newsletter. If negotiations started earlier, and there were more cost savings to the government from lower prices, that would result in lower returns to the innovator and investors. If higher returns were available for treatments that targeted populations that were not subject to government price negotiation, then investors and innovators may have more incentive to invest in and develop products in those populations.

Over the long-term, this could result in fewer new drugs for the Medicare population. It’s important to remember two things. One, drugs are often associated with cost offsets, such as a pill that prevents heart attacks. And two, the vast majority of new drugs only have high prices for a finite period of time (see the “We Did It Again” section). After the patent protection period, generic or biosimilar competition should enter and substantially reduce the price. But generic and biosimilar competition can only enter if there is a branded drug first. So fewer drugs could potentially increase costs over time. Yes, the government could increase their short-term savings by negotiating prices sooner, but are we confident there would be savings over a longer time horizon? I am not

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.