Generic competition after the patent period drives down healthcare spending

RAPID FIRE

We launched the Leerink Center for Pharmacoeconomics (CPE) three months ago. To celebrate that, and to provide content not related to the 15 drugs selected for Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, I want to answer the three questions I always get about CPE.

- What are you trying to do?

There is increased scrutiny around drug prices and increased emphasis on justifying drug prices with a value proposition. We want to add to those conversations with evidence around not only the health impacts, but also the broader societal impacts of healthcare innovations. Also, people focus on the price of a drug during its patent period when the price is high, but the system is designed so eventually the price should fall off a cliff. We want to add to those conversations with evidence around a drug’s price over its lifecycle.

- Are you trying to make drug prices even higher than they are today?

No. Although we examine specific drugs in our CPE Exclusives, our intent is not to suggest a price. The three drugs we have looked at in our CPE Exclusives have already had a price set by the market. Rather, our intent is to see what health and non-health outcomes we (i.e., society) might get from the healthcare innovation. Economic models can be powerful tools to extrapolate and synthesize evidence and explain what a healthcare innovation might do for patients, caregivers, the health system, and society.

I want to examine ways to improve efficiency while balancing the incentives for healthcare innovations (which can become extremely efficient especially after their patent period).

This month there was an analysis by the Berkeley Research Group that examined the complexity of the pharmaceutical supply chain and how only half of the total spending on branded drugs goes to the innovator. We also saw this month an interim report that suggested some specialty generic drugs are massively marked up (by thousands of percent!).

This suggests there are ways to reduce total spending on drugs (e.g., reducing perverse incentives, ensuring prices fall off a cliff after the patent period) even without reducing the amount that goes to the innovator to pay back their investment in the innovation.

- Why did you want to do this?

Over the last few years, I have been fortunate to engage with healthcare investors and development stage biotech companies. From these conversations, I have started to learn how they assess potential new treatments and what informs their decision making about what to develop and what to invest in. I approach these conversations with a background in pharmacoeconomics, and I have been surprised how different the modeling and approach to decision making in the healthcare investing world is from the modeling and approach to decision making in the pharmacoeconomics world.

In the healthcare investing world, market size, expected price changes (from competition during and after the patent period), and portfolio thinking (fund a portfolio of drugs in development knowing that some could be successful, some could not be successful) are core considerations. These are not core considerations in my world of cost-effectiveness analysis.

In a cost-effectiveness analysis, market size is rarely quantitatively considered. The outcomes and the analysis would be the same if it was for a condition that had 3 million people or 3 thousand people. Some have suggested a higher cost-effectiveness threshold for orphan drugs compared to non-orphan drugs, but a consistent recommendation has not been implemented in standard practice.

In a cost-effectiveness analysis, it is very rare for expected price changes to be considered. Peter Neumann and colleagues found that less than 5% of published cost-effectiveness analyses include assumptions about future price changes.

In a cost-effectiveness analysis, drugs that don’t make it to market are not considered. A cost-effectiveness analysis is focused on one drug and is typically done for those that are expected to be approved or were recently approved.

Pharmacoeconomics and healthcare investing are both important to the healthcare industry. Pharmacoeconomics can provide evidence to promote efficiency, and I think we can all agree that the efficient use of resources is important. Healthcare investors can provide expertise and money to bring new innovations to market, and I think we can all agree that healthcare innovation is essential.

However, pharmacoeconomists and healthcare investors have largely been operating separately despite drug pricing being important to both. Collaboration and shared understanding between the two could only help us get closer to an efficient system that incentivizes healthcare innovation.

I want to help build that bridge between health economics and healthcare investing.

WE DID IT AGAIN

Although we are all fixated on the next set of small molecule drugs selected for Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, we want to highlight real-world examples of how generic competition substantially reduced drug pricing for small molecules after their patent protection period.

Because of the pharmaceutical market design, branded drugs will likely become cheap generics that can benefit society long after their patent protection period. Let’s look at Cymbalta (duloxetine), a small molecule drug used to treat depression and other conditions. Cymbalta was first approved in 2004 to treat depression and diabetic neuropathy. In 2007, it was also approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In 2012, it was the manufacturer’s best-selling drug bringing in nearly $5 billion in sales.

On December 11th, 2013, the US patent expired for Cymbalta. On that same day, the FDA approved six generic versions of duloxetine, paving the way for price competition to hit immediately.

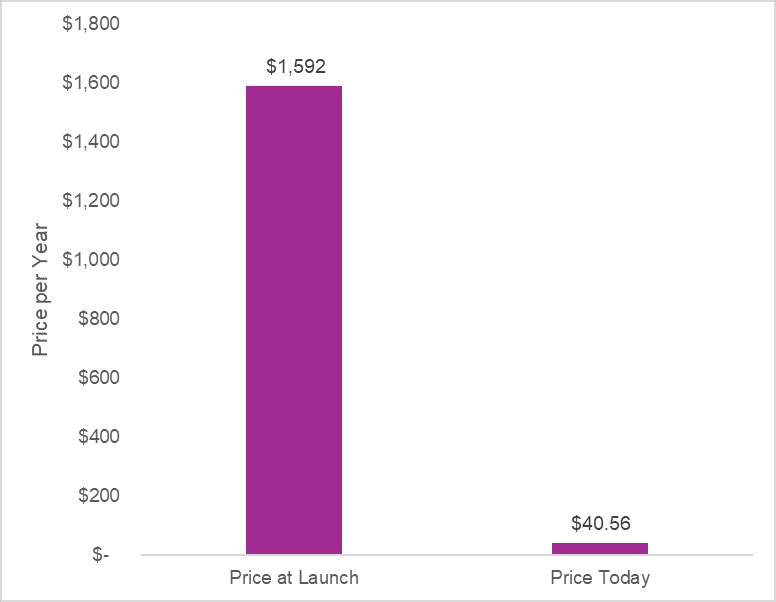

Adjusted to present value, Cymbalta was launched at an annual price of $1,592. Today, the annual price for generic duloxetine is $40 at the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company. This represents a 97% discount from the branded launch price.

This is how the system is designed to work. After the patent protection period for Cymbalta, generic versions entered and dropped the price per pill to literally pennies. As designed, the price fell off a cliff after patent expiry. The generic manufacturers ate up the branded manufacturer’s market share. The branded manufacturer had to come to the market with other new innovations that were still in their patent protection period to keep making money. Society got two things: 1) low-cost generic versions of duloxetine and 2) new innovations for other conditions that were brought to the market.

Policies that promote generic competition and uptake after the appropriate protected period can reduce healthcare spending without disincentivizing innovation.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.