We cannot detect if there is a market failure at 9 years

TURN THE PAGE

Last week, we released a Center for Pharmacoeconomics Special Report examining the real-world market dynamics of 15 drugs—10 small molecules and 5 biologics. Each of the drugs had been identified in a 2013 Fierce Pharma report as “Drug Launch Superstars”. We looked at the drugs from their report for two reasons: 1) it represented a list of drugs selected by an external source and 2) it included drugs that had been in the market for 12 to 16 years by the time of this report posting (the biopharmaceutical market design is set up so that a drug can be marketed without generic or biosimilar competition for around 14 years).

Briefly, here is what we described in our report.

Supplemental Approvals. Even after a drug is initially approved, manufacturers often invest in research to support additional indications, expanded populations, earlier lines of therapy, superiority over other treatments, or new formulations, dosages, or delivery methods. At the time of this report posting, 13 of the 15 drugs (87%) had at least one supplemental approval. Across the 15 drugs, there was an average of 4.5 supplemental approvals per drug.

These supplemental approvals require the drug manufacturer to invest in post-approval research and are beneficial for society and the stakeholders within the healthcare system.

Considering additional indications specifically, an additional indication results in a new approved treatment option for patients. For drug manufacturers, an additional indication can result in more revenue. For payers, an additional indication can increase the number of drugs approved for a condition, which can result in more price competition. And for society, additional indications usually have a shorter period of time that is under patent protection (i.e., when drug prices may be “high”) and thus a shorter time to generic/biosimilar entry (i.e., when drug prices should drop). Other types of supplemental approvals such as new routes of administration have their own set of stakeholder benefits.

To summarize, market incentives existed for the manufacturers to invest in post-approval research in pursuit of subsequent approvals which is a win-win for the manufacturer and for society.

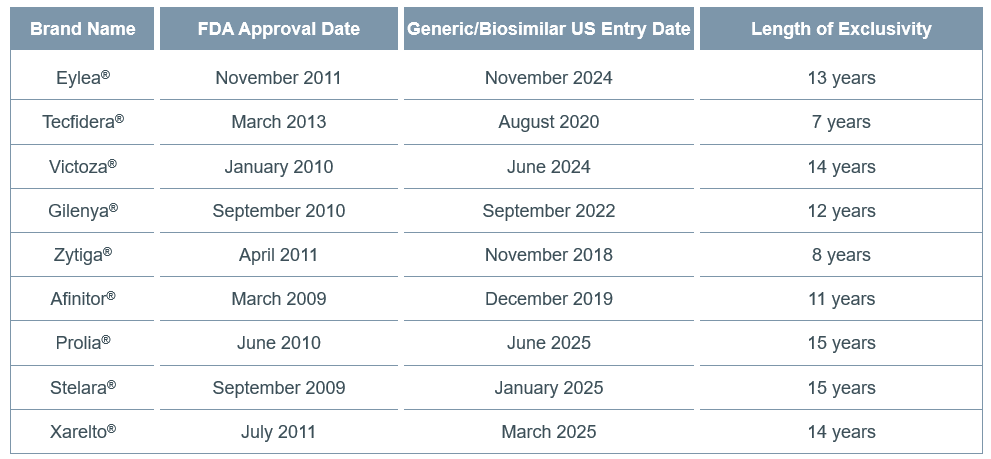

Duration of Exclusivity. At the time of this report posting, the majority (60%) of the drugs were already facing generic or biosimilar competition. For the 9 drugs that already had a generic/biosimilar in the US market, we estimated the length of exclusivity as the time between initial approval of the branded version of the drug and the US market entry of a generic/biosimilar version. Table 1 reports these length of exclusivity estimates.

Table 1. Length of Exclusivity for the 9 Drugs That Have Already Lost Exclusivity

Of the 9 drugs with known generic/biosimilar entrants at the time of this report posting, the shortest time to generic/biosimilar competition was 7 years and the longest time to generic/biosimilar competition was 15 years. Drugs with longer exclusivity periods tended to have more supplemental approvals. Although Prolia® and Stelara® (both biologics) had exclusivity periods [slightly] greater than 14 years, they each also had multiple supplemental approvals. All of the drugs with an exclusivity period greater than 14 years also had at least one additional indication.

The remaining 6 drugs were assumed to still be in their exclusivity period as a generic/biosimilar had not yet entered the US market. Table 2 reports the current time in market (i.e., calculated as the time between initial FDA approval and posting of this report), along with the molecule type and number of supplemental approvals, for the remaining 6 drugs.

Table 2. Time in Market and Supplemental Approvals for Drugs Still Under Patent Protection

Of the 6 drugs that had not yet faced generic/biosimilar competition at the time of this report posting, only one had been in the market for 14 years or more. When interpreting or critiquing this number, I believe it is also important to consider that the manufacturer has invested in post-approval research and development to support 13 supplemental approvals over its time in the market—the most recent of which was received only two months ago (FDA approved as a first-line treatment for unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma in combination with nivolumab in April 2025).

To summarize, market incentives existed for generics and biosimilars to enter the market as quickly as possible. Six of the drugs had not yet faced generic/biosimilar competition, but only one had been in the market for more than 14 years (and had invested in substantial post-approval research over this time). Some generics entered much earlier than 14 years. Ensuring generic and biosimilar competition after the appropriate protected period is essential to promote ongoing innovation and lower drug costs.

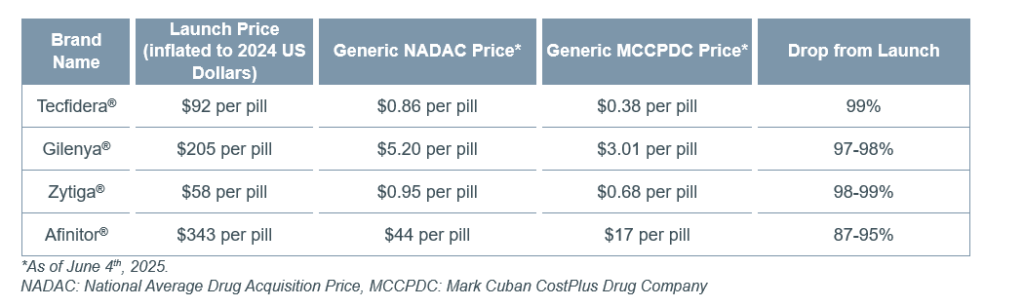

Post-Exclusivity Price Drops: For the subset of drugs we examined that had a generic version with public price estimates available, substantial price drops were already observed. For the four drugs that had already had a generic in the market for more than one year, the generic price was 87% to 99% lower than the branded launch price (Table 3).

Table 3. Post-Loss of Exclusivity Prices Versus Launch Price

The price drop observed to date for liraglutide (Victoza®) has been more subtle (2% to 45%)—potentially due to it facing generic competition for less than a year and because it is a pre-filled pen injector which might be harder to genericize and/or have higher cost of goods sold. Public price estimates could not be found for the biosimilars for Prolia®, Stelara®, and Eylea®.

To summarize, generic and biosimilar market competition is capable of producing substantial drops in prices. Promoting generic/biosimilar market entry and uptake after the appropriate protected period can meaningfully reduce a drug’s price while preserving the incentives for innovation.

SO WHAT

As illustrated above, a drug has a variety of market incentives and dynamics over its lifecycle, and it is critically important these are acknowledged when critiquing prices and developing policies.

It has become increasingly common to critique a drug’s price over its exclusivity period. However, a drug has an entire lifecycle characterized by different time periods that are often omitted from these conversations. First there is the drug development period that is characterized by research and development in pre-clinical and clinical trials and regulatory submissions. This can take 10-15 years and heavily relies on private investment. For the few drugs that receive regulatory approval, there is the exclusivity period in which the drug can be marketed without generic or biosimilar competition in order to pay back the investors and innovators for their invention. This is around 14 years. And then after the exclusivity period, generic/biosimilar versions can enter the market to substantially drive down prices and stay in the market forever.

These distinct periods, market-based pricing over the time-limited patent period, and market incentives for generic/biosimilar entry characterize the US biopharmaceutical industry, drive ongoing innovation, and support generic and biosimilar competition to drive down costs.

The real-world examples we looked at in our CPE Special Report illustrate how these market-based incentives work to support supplemental approvals (which should be a win-win for the manufacturer and society) and the entry of generic/biosimilar competition (which should result in substantial price drops). Importantly, I am not suggesting what we report for the 15 drugs above is representative for all drugs—the list of drugs evaluated were dubbed as “drug launch superstars”—but they give us a glimpse into the reality (and dynamics) that the market creates.

Everyone agrees that a drug’s price needs to eventually drop—this keeps companies and investors continuously developing new drugs to replace revenue and creates low-cost versions of drugs for society. The market design of the biopharmaceutical industry is set up to promote this.

However, there may be instances where the market does not work as it is intended to. If the market incentives for generic/biosimilar entry don’t work to substantially drive down a drug’s price, policies that target these instances may be necessary. Maybe the drug is hard to “genericize”, or the time without generics/biosimilars is inappropriately long, or the generic/biosimilar versions are not gaining market share, or the generic/biosimilar versions are excessively marked up above their cost of goods sold. These are things policy may need to target.

Most biopharmaceutical companies and investors understand the need for some policing of this. When the Inflation Reduction Act was first bubbling up, I heard many in the industry completely understand (even support) some form of price regulation around 15 years after launch. The market design should get the desired outcome (low-cost versions of drugs) around 14-15 years after initial approval. If it hasn’t achieved this after say 15 years, a federal policy to provide us “insurance” to achieve our goal could be beneficial.

The struggle comes in with the timing of the government price regulation in the Inflation Reduction Act (9 years for small molecules and 13 years for biologics). These clocks mean the intervention in the market occurs before the 14-year clock that the market has been working toward. Intervening before the 14-year clock risks attempting to fix things that aren’t broken.

Many in the industry have conceded with the 13-year time clock for biologics and essentially say it is close enough to 14 years (although they might be saying “close enough” for revenue received rather than “close enough” to detect a market failure). However, the 9-year time clock for small molecules is not “close enough”. We cannot detect if there is a market failure at 9 years.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.