Turns out we weren’t fooled

TURN THE PAGE

Our Center for Pharmacoeconomics (CPE) Exclusive suggested that Tecfidera’s US market-based price over its exclusivity period was likely a bargain, price increases and all.

In the CPE Exclusive we released yesterday, we presented estimates of the cost-effectiveness of Tecfidera® (dimethyl fumarate, developed by Biogen Inc.). Dimethyl fumarate was approved in 2013 for relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. Upon launch, the manufacturer priced a year’s worth of treatment at nearly $55,000 (in 2013 US dollars). The high price was a topic of discussion. Over the period of exclusivity, prices continued to increase, reaching an annual wholesale acquisition cost of nearly $100,000 (in 2020 US dollars) at the beginning of 2020. However, today, generic dimethyl fumarate can be purchased for less than $500 per year from the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company.

Drug prices should only be high for a finite period, and this is important for policy making and for critiquing drug pricing. It also matters for cost-effectiveness analysis, which is used by some health systems to inform decision-making around coverage and reimbursement. Although these analyses typically forecast costs and consequences far into the future—often decades—they almost never account for future price changes. Rather, it is conventional practice to keep a drug’s price constant over the entire time horizon, ignoring expected price changes over time.

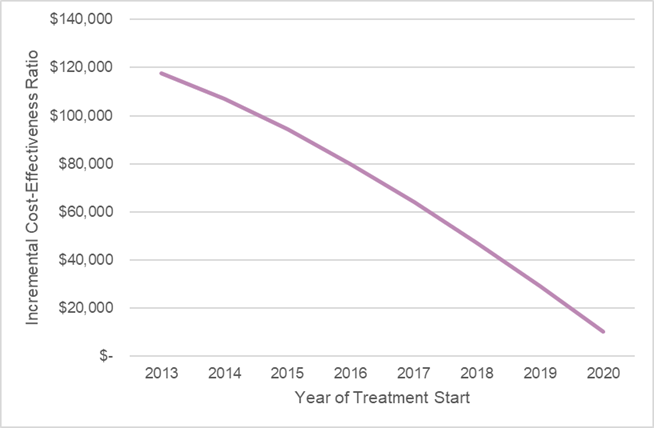

In our most recent CPE Exclusive, we estimated the cost-effectiveness of dimethyl fumarate at launch assuming static pricing (i.e., the conventional approach) and then we estimated the cost-effectiveness assuming dynamic pricing using the real-world price increases over the exclusivity period and the current generic price after the exclusivity period.

When evaluating dimethyl fumarate at launch under a conventional approach that assumed static pricing, its cost-effectiveness estimate was approximately $230,000 per equal value life year (evLY) gained. This would likely be interpreted as not cost-effective if using commonly used thresholds for cost-effectiveness. Based on this conventional approach, the price would need to be discounted 40-60% to meet those commonly used thresholds.

However, incorporating the price dynamics for a single cohort at launch resulted in acost-effectiveness estimate of approximately $118,000 per evLY gained. This could be interpreted as cost-effective if using commonly used thresholds for cost-effectiveness. (Note: Research around thresholds—and potential changes to the threshold if incorporating price dynamics—is ongoing. Relatedly, the optimal proportion of the “value” that should be allocated to the manufacturer versus society is also a topic of ongoing debate. We will discuss this more in an upcoming newsletter.)

The cost-effectiveness would continue to improve for cohorts that started treatment after the year it was initially launched, as the proportion of the time on generic dimethyl fumarate would increase. The figure below reports the cost-effectiveness estimate for different cohorts that started treatment during each year of the exclusivity period.

Source: Leerink Center for Pharmacoeconomics (CPE) dimethyl fumarate model.

The purpose of our Exclusive was to demonstrate the importance of considering a drug’s price over its lifecycle. In reality, a drug’s price should only be “high” for a period of time, and we believe this must be considered when a drug’s price is being evaluated and judged. Health systems that rely on cost-effectiveness analysis to inform decision-making, yet keep the drug’s price constant over time, can misrepresent the incremental costs and misinform decisions.

Although the US market-based price for Tecfidera was higher than the “cost-effective” price suggested by conventional methods (which hold drug pricing constant over time), we weren’t fools for paying the higher price. The “high” price we paid over the exclusivity period incentivized generic equivalents to enter the market to substantially drive down prices and incentivized the development of new, potentially even more effective, treatments for people living with multiple sclerosis.

Read our full report-to understand the model inputs and assumptions that informed our analysis.

WE DID IT AGAIN

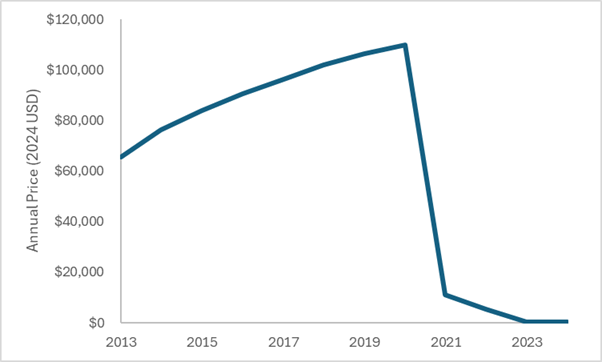

Expensive branded small molecule drugs can eventually become cheap generics that can benefit society long after their patent protection period. Let’s look at dimethyl fumarate. Dimethyl fumarate was approved in 2013 at a launch price of nearly $55,000 (in 2013 US dollars). Over the period of exclusivity, prices continued to increase, reaching an annual wholesale acquisition cost of nearly $100,000 (in 2020 US dollars) at the beginning of 2020.

The first generic version of dimethyl fumarate entered the market in late 2020. Shortly after, there were more than ten manufacturers that were making generic versions of dimethyl fumarate. Within six months of generic competition, the median wholesale acquisition cost for generic dimethyl fumarate was less than 90% of the branded wholesale acquisition cost.

Today (only 12 years after Tecfidera was approved) generic dimethyl fumarate can be purchased for less than $500 per year from the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company. This represents more than a 99% discount off the launch price. As designed, once generic competition entered, the price fell off a cliff.

The figure below plots estimates of the annual wholesale acquisition cost of dimethyl fumarate over the exclusivity period and estimates of generic pricing after the exclusivity period. All costs have been adjusted to 2024 US dollars.

The system worked as designed. Society paid back the innovator over a period of time and then the price substantially dropped. We must find a way to think long-term when judging the prices of drugs.

And, yes, not all versions of dimethyl fumarate in the market today are as inexpensive as the source I used for post-exclusivity pricing in the economic model built for our CPE Exclusive. I would argue that in a system that needs to find efficiencies while ensuring incentives for innovation, that seems like a place to look.

SO WHAT

There is ongoing debate about what value elements should be included in cost-effectiveness analyses, what threshold to use for cost-effectiveness analyses, and what is the optimal share of a treatment’s value that should be allocated to the manufacturer versus what should be allocated to society. Those debates are unlikely to be resolved anytime soon.

However, in a field where it is hard to find universal agreement around “value”, I think nearly everyone would agree that cost savings are a win. (Please don’t interpret this as me suggesting that is the only way to “win”. I am not. I am simply suggesting that most people would agree that a drug that reduces costs is a good thing.)

The evidence for dimethyl fumarate suggests that it reduces relapses and slows the progression to costlier disease severity states. Both of these things can translate to cost savings for the healthcare system. We saw this in our economic model—the per-person lifetime non-intervention health system costs were approximately $50,000 lower in those treated with dimethyl fumarate (even accounting for the longer length of life).

Once generic competition entered the market and reduced the price close to its cost of goods sold, the cost of the drug was less than the cost offsets it created in the health system. Therefore, dimethyl fumarate can save health system costs after the exclusivity period—in addition to increasing survival, improving patient quality of life, increasing productivity, reducing caregiver time, etc.

Innovation can reduce health system costs, but this often requires thinking beyond launch and beyond the initial exclusivity period. Adequate incentives for innovation must exist so we don’t miss out on the opportunity for long-term cost savings and/or improved health and non-health outcomes.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2025 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.