Generic drugs approved in 2022 saved $19 billion within a year

SAD BUT TRUE

Insurance coverage restrictions, although at times extremely frustrating for patient access, are proof that we have a market in the prescription drug industry. If applied appropriately, this can promote value and efficiency. Many believe that pharmaceutical companies can set a drug’s price at whatever price they want, but coverage restrictions show that is not the case. Even considering the patent and exclusivity protections of pharmaceuticals, and the lack of a central negotiator in the United States, insurance companies and their affiliates have mechanisms to negotiate through their ability to not cover some medicines or to cover medicines but with restrictions.

Even in Medicare Part D plans, where there are mandates that at least 2 drugs per drug category are covered and nearly all drugs for select categories (antidepressants, anticancer, etc.) are covered, there are still mechanisms to negotiate. Coverage doesn’t mean coverage without restrictions.

A team of researchers at GoodRx examined nearly 4,000 Medicare Part D plans. In 2024, the average Medicare Part D plan covered only 54% of prescription drugs and half of all covered prescription drugs had a restriction.

This is evidence that there are mechanisms to negotiate in the prescription drug industry. Now, no one will claim it’s a perfect market and there are perverse incentives that policies must address. We suggest that evidence around the societal value of an innovation, rather than some other misaligned incentive, should be considered within these negotiations to better balance patient access and system efficiency.

Importantly, I understand coverage restrictions are extremely frustrating for patient access. I will save my story on how an individual affiliated with my insurance called me and “educated me on the consequences to my child’s health of me not picking up my daughter’s inhaler”—while I had been on the phone for over five hours that week trying to navigate the web of prior authorization to figure out where the holdup was. We will dedicate future newsletters to discussing ways to balance patient access and system efficiency.

WE DID IT AGAIN

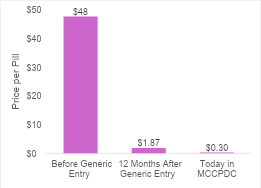

Expensive branded drugs will likely become cheap generics that can benefit society long after their patent protection period. Let’s look at Latuda (lurasidone hydrochloride). Latuda was approved in 2010. In 2023, 13 years after approval, generic versions entered the market. Within twelve months of generics becoming available, the price had dropped 99%. As of October 30th, 2024, the price per pill at the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC) was approximately $0.30 per pill (per pill average across all strengths using the 90 count package). You might look at the graph and be surprised at how quickly and steeply the price dropped, yet this is not unexpected. This is exactly how the system is supposed to work.

Branded drug prices should only be high for a finite period. This is important for policy making and for public perception around drug pricing. It also really matters for cost-effectiveness analysis. As mentioned during last week’s newsletter, cost-effectiveness analyses almost never account for future genericization. Rather it is conventional practice to keep a drug’s price constant over the entire time horizon, ignoring expected price changes due to eventual genericization. In the case of lurasidone hydrochloride, this would substantially overestimate the treatment costs.

In a Health Affairs Forefront commentary, I, along with my co-authors Dr. Peter Neumann, Dr. Josh Cohen, and Dr. Jon Campbell, argue that cost-effectiveness analyses should incorporate these future price changes to more accurately reflect drug costs over time. Without accounting for these future price changes, cost-effectiveness analyses can misrepresent the drug’s costs over time and “may incorrectly suggest the new drug represents unfavorable value”.

TURN THE PAGE

The 742 generic drugs approved in 2022 saved $19 billion within a year. These estimates are from a new report released by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration. There is much to be excited about in the report.

First is the magnitude of the number of approved abbreviated new drug applications (ANDAs) in one year—742. That’s more than two per day on average. These 742 ANDAs are for 407 unique drugs, and 32 “first generics” of which 18 are for new molecular entities.

Then there’s the savings. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration estimates the price declines saved $18.9 billion in 12 months. And here’s the exciting part—cost savings should continue to accrue over time as the generic versions remain in the market and increase in market share.

Remember lurasidone hydrochloride, the case study we explored in the “We Did It Again Section”? Its initial cost savings from generic entry are captured in these data. When reading the “We Did It Again Section”, some might have questioned whether anyone was still using lurasidone hydrochloride or if more novel branded drugs dominated the market by the time generic versions entered the market. However, the report by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration suggests that there were still 325,000 prescriptions filled for lurasidone hydrochloride—per month. Some might have also questioned if the generic versions were successful in gaining any market share or if the branded product dominated the market. The report also suggested that the generic market share was 90% of all filled prescriptions.

As mentioned above, this is how the system is supposed to work, and we should all do our part to make sure the system works as intended. I don’t think anyone would deny that there have been some bad actors that have price jacked drugs or taken advantage of the patent system. These actions are destructive threats to the system and policies should be in place to safeguard the system against them.

We are also living in an era in which some innovation is simply harder or impossible to “genericize”. Policies should also exist to ensure an innovation’s price isn’t high forever so society can access the innovation at prices closer to their cost of goods sold after a sufficient protected period.

As mentioned in the first newsletter, there are serious inefficiencies in the health system that need to be addressed, and there are situations in which the system does not work as intended or bad actors have taken advantage of the system. Targeting and preventing system failures is one such way to promote efficiency while balancing incentives for research and development.

SEEK AND DESTROY

Some have suggested replacing the private sector funding of pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) with the public sector. An argument for this thinking is that if the government funded all R&D, there might not be profit motivation which could translate into lower prices and maybe even more innovation in rare diseases.

However, a recent peer-reviewed study published by Proudman and colleagues explains how “replacing such investment while maintaining the current innovation output in terms of approved therapies would necessitate substantial increases in taxpayer financing”. They estimated that the annual replacement cost would be 25 times the estimated annual budget that the NIH dedicates to clinical trials for pharmaceuticals.

In addition to some eye-opening estimates of R&D and replacement costs, the study also provides commentary and a summary of literature on the potential impact of public versus private funding on welfare, efficiency, innovation, and politics.

Dr. Ge Bai writes in Forbes, “Private investment in biotech is a sweet deal for the public”. She explains why in the article. Private investment in biotech means that for all of those ideas and innovations that never make it to approval (see last week’s newsletter where we note the approval rate of a Phase I drug is around 8%), investors face the risk rather than the government and its taxpayers. For those ideas and innovations that do make it to approval, the investors get a financial return, and taxpayers get a new treatment that has been deemed safe and effective.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2026 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2026 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosures

The Center for Pharmacoeconomics (“CPE”) is a division of MEDACorp LLC (“MEDACorp”). CPE is committed to advancing the understanding and evaluating the economic and societal benefits of healthcare treatments in the United States. Through its thought leadership, evaluations, and advisory services, CPE supports decisions intended to improve societal outcomes. MEDACorp, an affiliate of Leerink Partners LLC (“Leerink Partners”), maintains a global network of independent healthcare professionals providing industry and market insights to Leerink Partners and its clients. The information provided by the Center for Pharmacoeconomics is intended for the sole use of the recipient, is for informational purposes only, and does not constitute investment or other advice or a recommendation or offer to buy or sell any security, product, or service. The information has been obtained from sources that we believe reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should not be relied upon as such. All information is subject to change without notice, and any opinions and information contained herein are as of the date of this material, and MEDACorp does not undertake any obligation to update them. This document may not be reproduced, edited, or circulated without the express written consent of MEDACorp.

© 2026 MEDACorp LLC. All Rights Reserved.